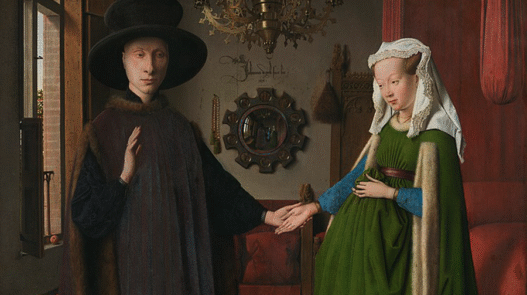

At the heart of the painting hangs one of art history’s most haunting details: the convex mirror. In its tiny circle, the world expands. The reflection reveals not just the backs of the couple but also two other figures entering the room, witnesses, perhaps, or Van Eyck himself. Around the mirror’s edge, miniature medallions depict scenes from Christ’s Passion, transforming the domestic into the divine.

Here, the mirror becomes the eye of God, omniscient and eternal, reminding viewers that all human actions unfold before divine vision. In Van Eyck’s hands, light itself becomes a theological metaphor, a visible manifestation of truth.

A Room as a Universe

The setting feels domestic

An intimate chamber bathed in the golden hush of afternoon light. But in the 15th century, home was not only private space; it was a spiritual theatre. The interior becomes a sacred stage, where ordinary gestures mirror holy rites.

The small dog at the couple’s feet, for instance, is no mere pet. It stands for fidelity and loyalty, its watchful gaze echoing the unseen vows between the man and woman. The placement of their hands, joined but not quite touching, speaks to both connection and restraint, the delicate boundary between affection and propriety in a world governed by moral codes.

On the dog symbolising fidelity and loyalty:

“The little dog at her feet is a symbol of fidelity, loyalty…”

The National Gallery notes: “In a brick-built house… almost every object conveys the event’s sanctity, specifically, the holiness of matrimony.”

The Silent Vows of Light

Few paintings whisper secrets quite like Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434). At first glance, it looks deceptively simple: a wealthy couple stands hand-in-hand in a richly furnished room. Yet, beneath that stillness lies a symphony of symbols — every fold of fabric, every glint of glass, every flicker of candlelight carrying meaning.

In Van Eyck’s world, nothing is mere decoration.

Holding of Hands

The holding of hands (or more precisely, the joining of hands) in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) is one of its most symbolically rich and debated gestures.

It’s subtle, their hands don’t fully clasp; instead, Giovanni Arnolfini gently raises his right hand while grasping his wife’s left, but that small act carries layers of meaning.

Many scholars interpret the joined hands as a gesture of betrothal or marriage, an early visual record of a legal or spiritual union.

In the 15th century, the “joining of hands” (dextrarum iunctio) was a formal symbol of a wedding vow, used in both religious ceremonies and secular contracts.

As the National Gallery explains, “The candle burning in daylight symbolises the all-seeing presence of God, before whom the couple join hands.”

Newsletter

Most Taboo and Forbidden Symbolism Delivered Straight to Your Inbox

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

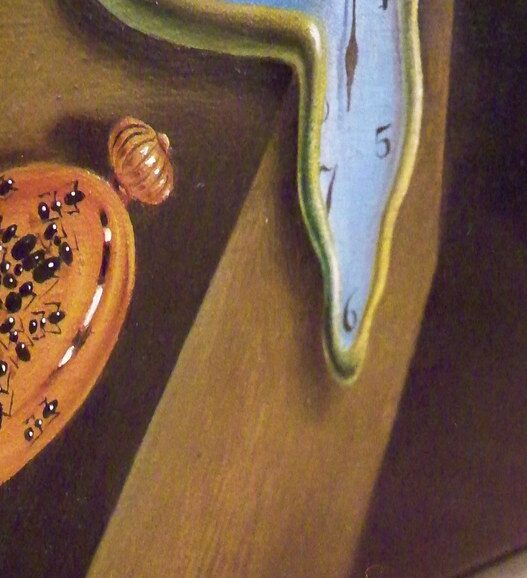

Light, Texture, and the Divine

Van Eyck’s technical mastery was revolutionary. The oil paint allowed for depth, translucence, and a sense of infinite detail. The gleam on the brass chandelier, the lush texture of the green gown, the soft fur of the dog, each rendered with devotional care.

That single candle burning in the chandelier, lit though it’s daylight, suggests the presence of God. It glows like the eternal flame of life and faith, hovering above the couple’s union.

Even the discarded shoes at their feet have weight: holy ground, where sacred vows are made, recalls the biblical moment when Moses removes his sandals before the burning bush.

My Thoughts

Encountering The Arnolfini Portrait is like stumbling into a quiet room polished with mystery, where every surface, cloth, wood, fur, glass, carries a hush of meaning. Van Eyck’s work isn’t simply a representation of two figures, but a stage on which domestic ritual, material wealth, and silent psychological drama play out.

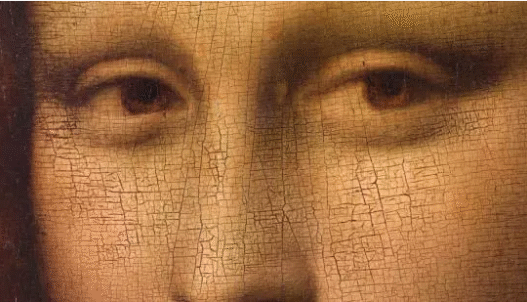

The couple stand in a richly furnished chamber, yet there’s a curious stillness to their posture. He lifts his hand in a gesture that lingers between greeting and oath, his gaze calm but distant. She stands with one hand held out, the other subtly touching the folds of her gown, an ambiguous pose that nudges us to ask: is she poised in devotion, in vulnerability, in hope? The reviewer describes her expression as “Mona-Lisa-like”: poised yet inscrutable

In the End, Everything Shines

The true miracle of the Arnolfini Portrait is that it feels alive.

Nearly six centuries later, the light still glimmers; the mirror still reflects; the candle still burns. Van Eyck immortalised not just two souls, but the very act of being seen, by each other, by the artist, and by eternity.

In that way, the painting is a mirror for us too: asking quietly, What does it mean to be witnessed — and remembered — in the light of time?