Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron is considered one of the most beautifully animated film on the decade.

After the passing of Isao Takahata in 2018, Hayao Miyazaki chose to shift the focus of the film toward the symbolic relationship between Mahito and the Heron. This new focus weaves together the surviving founders’ shared memories with Miyazaki’s personal experiences, exploring themes of acceptance, redemption, and the transformative power of creation.

The narrative also delves into coming of age, the process of grieving, and the responsibility of living for others.

Like Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, and Howl’s Moving Castle, it weaves complex imagery and layered meaning into its narrative and design, rewarding careful exploration through an artistic lens.

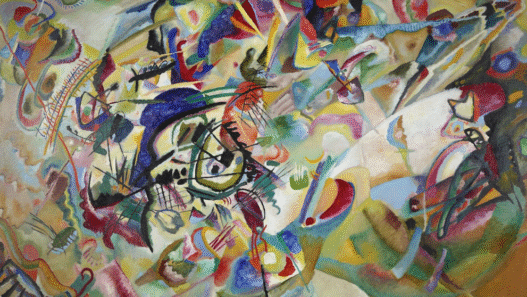

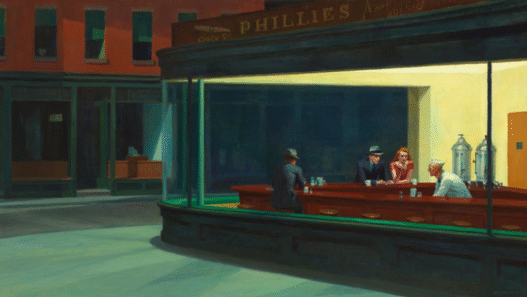

It’s no surprise that The Boy and the Heron draws deeply on artistic traditions, from classical Japanese art to modern surrealism. But when the past and present collide, which side is seared into our subconcious?

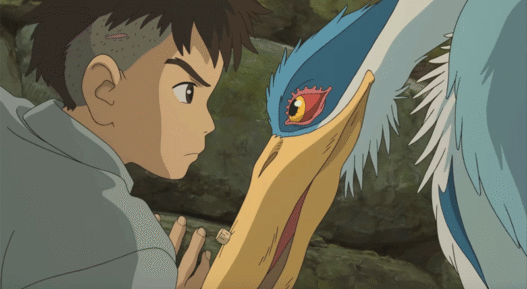

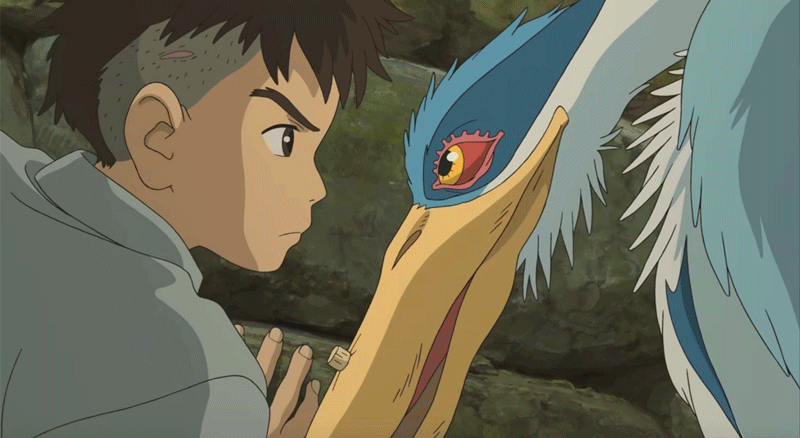

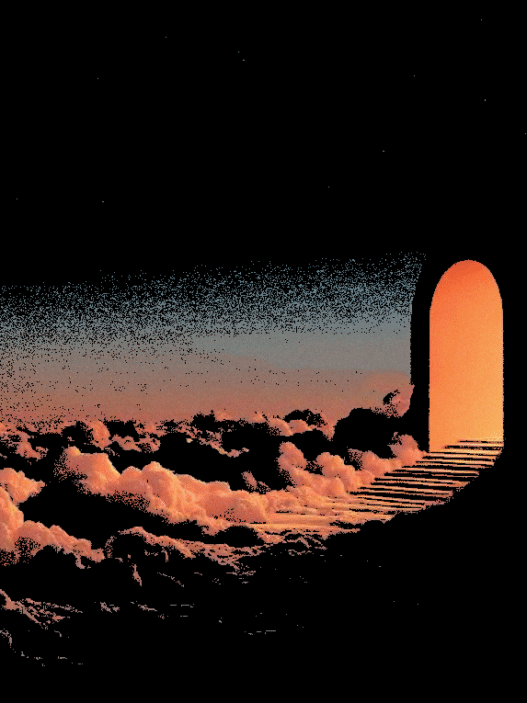

Cinematic Trailer:

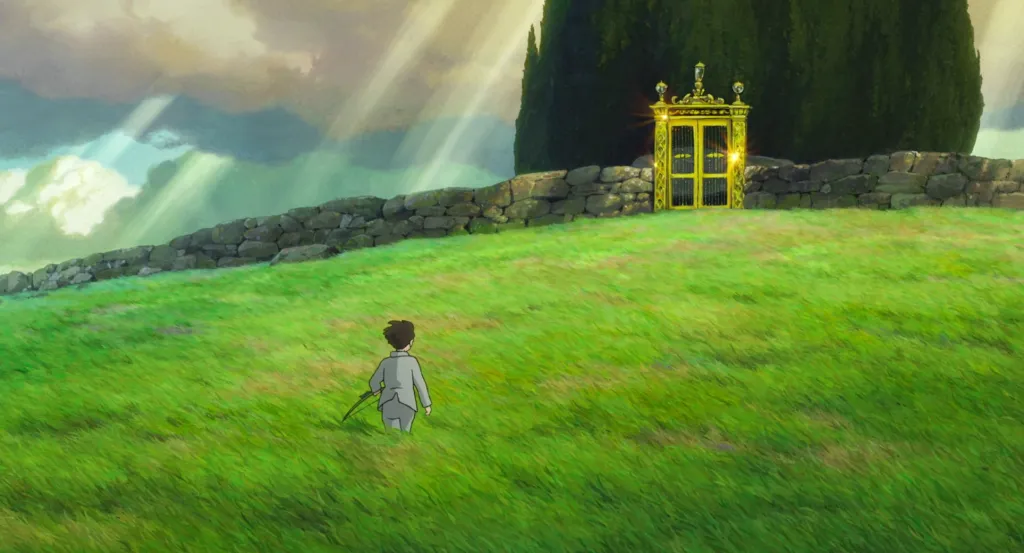

The Heron as a Guide

In this scene, the heron appears as a spiritual guide, leading Mahito into a realm that bridges the living and the dead. The heron’s presence underscores themes of death, transition, and the journey between worlds, aligning with its symbolic role in Japanese culture as a messenger between realms.

Miyazaki is not alone in layering symbolism so densely. Other films that share this rich visual and narrative depth include:

-

Spirited Away (2001) – Another Miyazaki masterpiece, where spirits, baths, and fantastical transformations act as metaphors for identity, consumerism, and the transition from childhood to adulthood.

-

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) – Guillermo del Toro’s dark fairy tale intertwines historical reality with mythic fantasy, using creatures, labyrinths, and tasks to explore trauma, innocence, and resistance.

-

The Holy Mountain (1973) – Alejandro Jodorowsky’s surrealist epic is a visual feast of allegory and symbolism, using striking imagery to critique society, spirituality, and human desire.

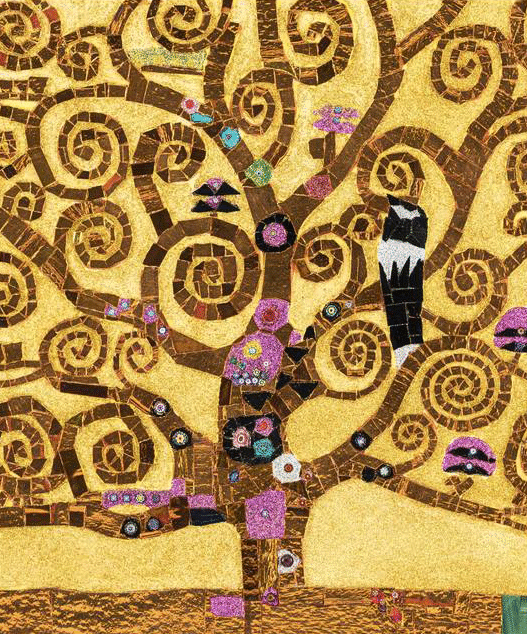

Objects and Symbols: The Language of Memory

Throughout the film, objects carry symbolic resonance. Personal items, relics, and architectural details serve as anchors for memory and history, reminding viewers that every detail is charged with narrative and emotional significance.

This echoes how still-life paintings in both Eastern and Western traditions encode stories, allegories, or moral lessons in everyday objects. The boy’s interaction with these symbols becomes a meditation on memory, loss, and the passage of time.

Who are the Warawara?

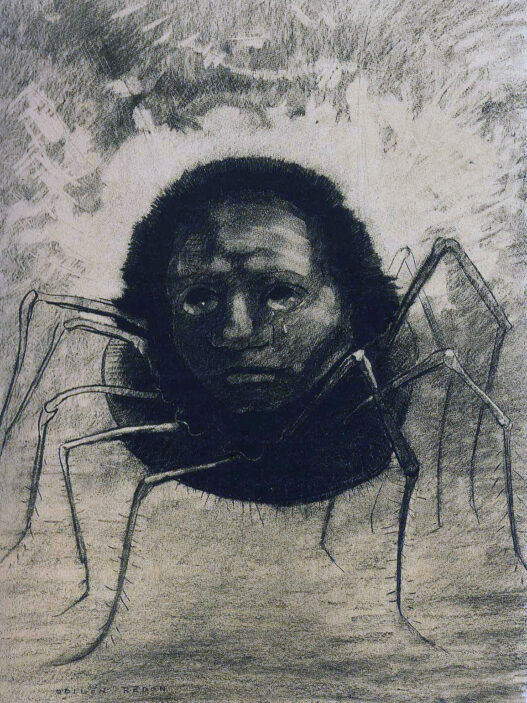

The Warawara’s existence and their interactions with other creatures in the Sea World underscore themes of creation, destruction, and the inherent struggles of life. Their vulnerability and the predatory nature of the pelicans highlight the delicate balance between life and death, as well as the harsh realities that new beings must navigate to find their place in the world.

They are in danger from pelicans in the other world, and some are even eaten or prevented from “ascending” or reaching birth. The idea of groups of souls, or life before birth.

Through the Warawara, the film explores the concept of life as a journey filled with obstacles and the constant interplay between creation and destruction. Their plight serves as a metaphor for the broader human experience, emphasising the importance of resilience and the will to survive amidst adversity.

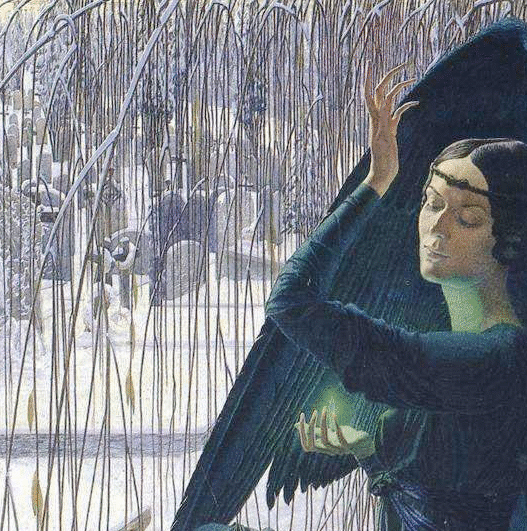

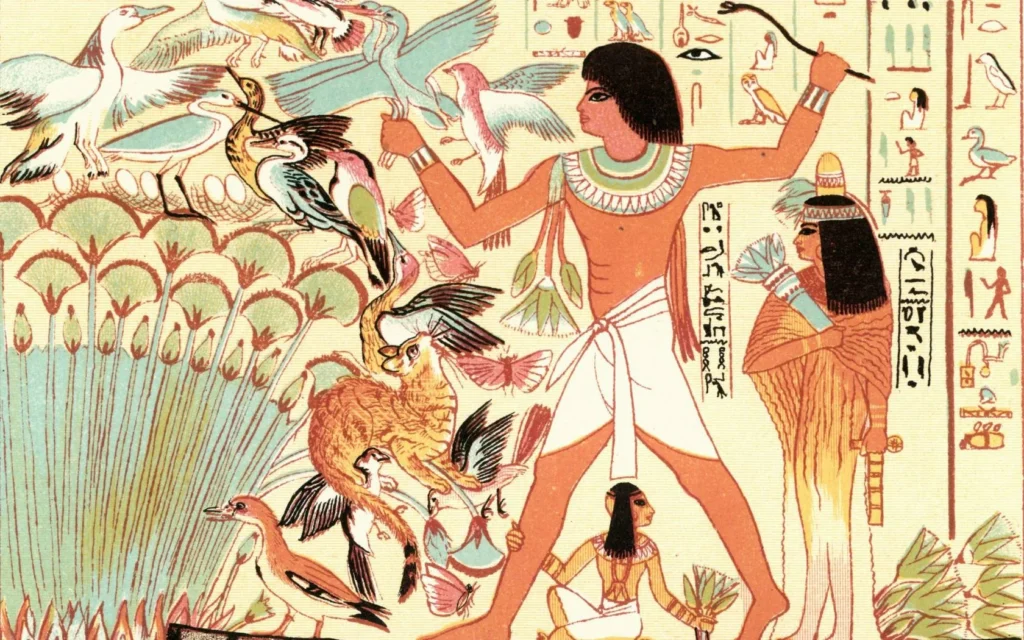

The Heron in Ancient History

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the heron was a powerful symbol of creation and renewal. Its call was believed to be that of the sacred Benu-bird, which heralded the beginning of time. The Benu-bird was closely tied to the Egyptian calendar and the concept of cyclical renewal, while a heron hieroglyph often represented the sun-god Ra. The Book of the Dead even contains spells intended to transform the deceased into the great Benu-bird. A double-headed heron symbolised prosperity and abundance.

In Greek mythology, the heron served as a messenger for Athena, the goddess of wisdom. In Homer’s The Iliad (translation by Robert Fitzgerald), a heron gliding through the night encourages Odysseus, inspiring his prayers to Athena. The bird’s cry was interpreted as a sign of guidance and divine favour. Linguistically, the name “heron” derives from the Greek word krizein, meaning “to cry out” or “to shriek,” reinforcing its role as a herald.

For the Aztecs, the heron played a foundational role in creation myths. The people were said to emerge from seven caves at the center of the earth to reach Aztlan, “the place of the herons.” The name Aztlan combines aztatl (“heron”) with tlan(tli) (“place of”), linking the bird to origin, emergence, and homeland.

In Chinese symbolism, the word for heron (lu) is a homophone for “path” or “way.” Herons often appear alongside lotus flowers in charms and artwork, conveying blessings such as, “May your path be ever harmonious,” merging the ideas of journey and continuous harmony.

Among the Iroquois, the blue heron was considered a favourable omen, particularly for hunters embarking on a journey. Its presence was interpreted as a sign of guidance, foresight, and protection.