Jenny Saville is a name that has endured the world of contemporary art. Her canvases are unapologetic, visceral, and often confrontational, inviting viewers to confront the human body in ways that challenge societal norms and expectations.

But to truly understand Saville’s work, one must go beyond surface impressions and delve into the anatomy of her anatomy, how she dissects, reassembles, and transforms the human form.

Radical Approach to the Human Body

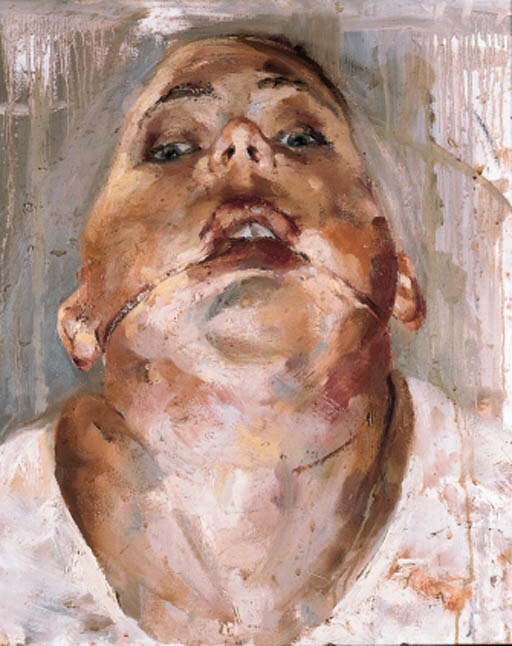

Saville’s work is remarkable for its focus on the flesh.

Throughout the years, painters have studied classical depictions of the body that emphasise beauty, symmetry, and proportion. Saville is determined to shine the lens on something else. The figures are massive, distorted, and sometimes grotesque.

She captures the textures of skin, the folds of fat, the stretch of muscles, and the sag of age, making her paintings an exploration of what bodies actually look like rather than what society dictates they should.

Her technique is rooted in traditional oil painting, yet the scale and intensity of her brushwork push the medium into a new realm. She layers paint thickly, scrapes it away, and reworks surfaces, creating forms that are both sculptural and painterly.

This method reflects her commitment to exploring the physicality of the body, not as an object of desire, but as a landscape of experience, vulnerability, and identity.

The Gendered Body and Societal Expectations

Saville’s focus is often on women’s bodies, particularly those that exist outside conventional ideals of beauty. In doing so, she challenges the viewer to reconsider ingrained cultural standards.

Her paintings confront the shame, fear, and fascination that society attaches to women’s flesh, whether it’s cellulite, stretch marks, or the natural curves of aging.

By amplifying and distorting these bodies, Saville does not mock or diminish them. Instead, she presents them with a heroic grandeur, demanding recognition and respect. Her work can feel uncomfortable, but that discomfort is intentional, it is a confrontation with the truth of human existence, stripped of cosmetic illusion.

Jenny Saville was born in 1970 in Cambridge, England, but grew up in Oxford. She comes from a family that valued education, and she was interested in art from a young age, though she didn’t immediately gravitate to painting the human body.

Early influences for Saville included classical figurative paintings like Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Saville herself has said she was aware of the way women were portrayed in media and advertising, and that she wanted to create work that reflected real, lived bodies, not idealised ones.

Symbolism in Three Jenny Saville Paintings

Seeing Saville’s work in person is one thing, but diving into the symbolism of her pieces is another journey entirely. Each painting feels like a conversation, between body, paint, and the stories we carry in our flesh. Here’s how three of her works spoke to me.

1. Propped (1992)

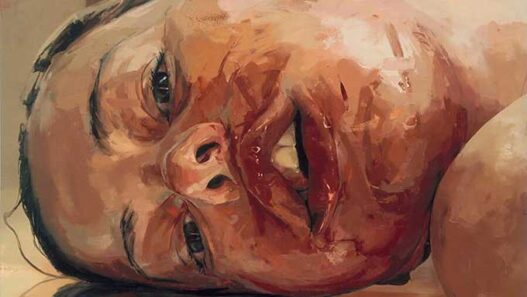

This painting hit me first with its sheer honesty. A massive nude reclines, twisted and unapologetic, her body spilling beyond the frame.

At first, I felt discomfort, then recognition. The total mass that extrudes in the middle, with giant hands digging into the flesh reminds me of scaffolding, contorted under a bridge. Saville exaggerates the fleshy folds and in doing so, she exposes vulnerability and resilience at the same time.

The symbolism is clear: this is the human body as both battlefield and sanctuary, carrying memory, experience, and identity in every curve. It’s messy, it’s raw, and it refuses to conform to any ideal.

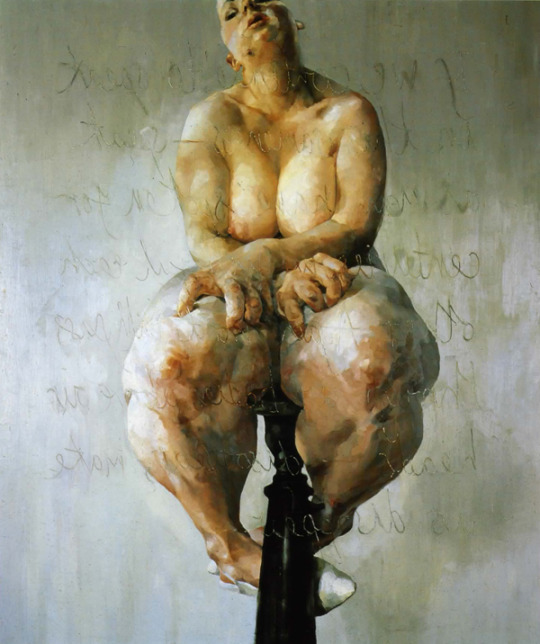

2. Branded (1992–93)

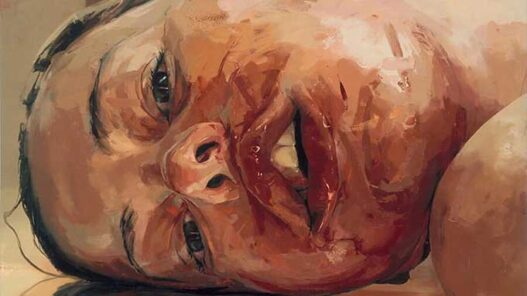

Here, the symbolism takes a darker, almost violent turn.

The figure’s skin seems marked, stretched, almost scarred. I remember standing in front of this one, feeling like the canvas was reading me as much as I was reading it.

The head slightly tilted back, exposing the soft underpart of the neck. In classical and modern art, a tilted-back head often carries erotic or intimate undertones, emphasising curves and soft forms. In this painting, however, the gesture evokes emotional and psychological depth, drawing the viewer into the subject’s inner experience rather than simply their physicality.

Yet there’s defiance here too; the figure isn’t hiding. She bears her marks like armor, claiming autonomy over her own flesh.

3. Fulcrum 1999

At first glance, it’s shocking. But look closer and you will find Saville isn’t interested in shock for its own sake. She’s challenging centuries of how the female body has been depicted in art, historically as passive, ornamental, or idealised. Here, the figures exist on their own terms. They are assertive, complex, and fully embodied. This is a common theme in Saville’s artwork.

The title Fulcrum is the pivot point of balance, the axis around which weight shifts.

And that’s exactly what Saville is doing: balancing, or perhaps unbalancing, the expectations society places on bodies with the reality of how bodies actually exist. The painting feels like a reclamation, a refusal to conform to narrow standards of beauty. The bodies avoid gravity and float between one another.

Anatomy as Expression

Through the anatomical lens, she explores identity, vulnerability, and mortality. The human body in her work is both universal and deeply personal: a vessel for experience, emotion, and history.

Interestingly, her paintings often evoke the style of medical illustrations, yet unlike clinical diagrams, they are imbued with empathy, rage, and intimacy.

The exaggerations in scale and form force the viewer to engage with the body in a way that is both analytical and emotional, making Saville’s work a meditation on the human condition itself.

Jenny Saville has become a defining figure in contemporary painting, influencing countless artists who seek to represent the body honestly and boldly. Her work resonates because it refuses to sanitise, idealise, or beautify, her anatomy is real, complex, and unflinching. In a culture obsessed with image and perfection, Saville’s canvases remind us of the power of truth, the poetry in imperfection, and the resilience of flesh.