John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) is celebrated as one of the finest portrait painters of his era, renowned for his striking realism, luminous brushwork, and impeccable technique.

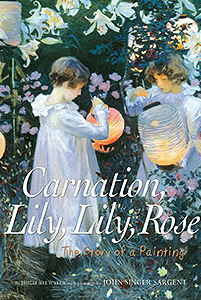

One painting stands out for its symbolic depth rather than portraiture: Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885–1886).

Fact: Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was painted entirely en plein air at dusk, with Sargent working for only a short window each evening to capture the delicate glow of lantern light against fading daylight. As summer ended, he even used artificial flowers to continue the painting.

According to Tate Britain, this careful attention to fleeting light is what gives the painting its signature luminous and magical quality.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

This enchanting work depicts two young girls lighting Chinese lanterns in a lush English garden at twilight. On the surface, it is a delicate scene of innocence and play, suffused with the soft glow of lantern light reflecting on flowers.

Yet beneath this idyllic image lies a rich tapestry of symbolism. The lanterns themselves suggest transience and the fleeting nature of childhood, while the lilies and roses are traditional symbols of purity, beauty, and the cycle of life. The interplay of light and shadow evokes a sense of mystery, capturing the fragile boundary between day and night, reality and imagination.

What is the inspiration?

One of the most direct inspirations came from a real event: in September 1885, Sargent went on a boating trip on the River Thames at Pangbourne with his friend, the artist Edwin Austin Abbey. During that trip, Sargent saw Chinese lanterns hanging in trees among lilies. This was the moment that sparked the image of glowing lanterns in a garden at dusk, a visual motif he later translated into Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose.

After the boat trip, Sargent spent time in Broadway, a village in the Cotswolds, staying with his friend Francis Davis Millet. He worked in Millet’s garden (or nearby) to bring his vision to life. Because he was painting “en plein air” (outside) and trying to catch a very particular light (dusk), he would only paint for a few minutes each evening, when the lantern glow and twilight matched what he saw on the Thames.

The Title and Musical Inspiration

The title Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose comes from a song. Specifically, it’s drawn from the refrain of an 18th-century song called “The Wreath” (sometimes “Ye Shepherds Tell Me”) by Joseph Mazzinghi.

The lyrics mention “A wreath around her head … Carnation, lily, lily, rose.”

Models and Personal Relationships

The two girls in the painting are Dolly and Polly Barnard, daughters of Sargent’s friend, illustrator Frederick Barnard. Originally, he had planned to use Katherine, Millet’s daughter, as a model, but he ended up replacing her for Dolly and Polly because of their blonde hair, which fit his vision better.

Symbolic Meaning

Putting all these inspirations together, scholars interpret Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose not just as a literal garden scene, but as symbolic:

The lanterns represent transience

The flowers (carnations, lilies, roses) are traditional symbols: lilies for purity, roses for love or beauty, carnations for fascination or distinction, giving a “flower-maiden” allegory.

Some interpretations (though more speculative) suggest subtle erotic symbolism: for example, the act of lighting the lantern “lighting a lamp” could be seen metaphorically (though this is debated).

The careful twilight lighting, the moment at dusk, underscores the ephemeral nature of innocence and beauty.

in Sargent’s Footsteps: A Conversation

The Story Behind the Lillies

According to British Art Studies, the way the lilies arc over the children and create a decorative, almost flat decorative space is something he later refined in Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose.

Sargent was strongly influenced by Impressionism, particularly the work and methods of Claude Monet. Monet’s dedication to painting en plein air and his fascination with capturing fleeting, atmospheric light deeply informed Sargent’s approach in Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. This influence is evident not only in Sargent’s commitment to painting outdoors at the precise moment of dusk each evening, but also in his broader interest in transient effects of illumination.

His sketch of Monet painting outdoors, Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood, further demonstrates Sargent’s admiration for and engagement with Monet’s techniques, reinforcing how Impressionist methods shaped the luminous, time-sensitive qualities of his own work.

According to research, Sargent was very particular about how his painting was displayed. He once noted that the warm, post-sunset light in which he painted didn’t always come through under gallery lights in London. Because of this, the painting is understood to “look best on a grey or foggy day” which, in my experience, won’t be hard find in London!

5 Symbolic Details to Notice When You’re Standing in Front of the Painting

The Lighted Lanterns as Childhood Innocence

The paper lanterns glowing at dusk symbolise the fragile, fleeting nature of childhood. Their warm, gentle light captures that brief moment between day and night, just as childhood exists between the phases of life.The Lilies as Purity and Transience

Lilies traditionally symbolise purity, but here they also represent the passing of summer. Their fading blooms echo the idea of innocence slipping away, making the scene feel both magical and slightly melancholic.Dusk as a Symbol of Transition

Sargent painted this en plein air, capturing that exact second when natural light shifts. Standing close, you can feel that symbolic threshold: not fully day, not fully night, mirroring the girls’ shift from childhood into awareness.The Ritual-Like Arrangement

The girls’ absorbed, gentle movement as they light the lanterns feels almost ceremonial. This creates a symbolic sense of a private, sacred world, children performing a quiet ritual adults are not meant to enter.Nature as Emotional Atmosphere

The dense garden encloses the scene like a protective cocoon. The flowers create a symbolic sanctuary, expressing beauty, safety, and the delicate world of childhood imagination that will eventually be outgrown.

How John Singer Sargent Painted Carnation, Lily, Lily

Sargent began Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose while staying with the painter F.D. Millet in Broadway, Worcestershire, shortly after moving to Britain from Paris. Initially, he used the Millets’ five-year-old daughter, Katharine, as a model, but soon replaced her with Polly and Dorothy (Dolly) Barnard, daughters of the illustrator Frederick Barnard, whose hair colour perfectly suited his vision. One of the few figure compositions Sargent ever painted outdoors in the Impressionist manner, he worked on it from September to early November 1885, then continued at the Millets’ new home, Russell House, during the summer of 1886, completing the painting around October.

Related Works to Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

Sargent’s close friendship with Claude Monet shaped much of his outdoor technique, and his sketch Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood reveals his direct engagement with Impressionist methods.

His own earlier experiments with twilight and outdoor light, such as Home Fields and Garden Study of the Vickers Children, show him gradually refining the interplay of natural light, floral colour, and childhood innocence. Together, these works trace the artistic path that culminated in the glowing, dreamlike atmosphere of Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose.

If this painting speaks to you, explore Sargent’s other light-focused works, such as Fumée d’Ambre Gris or his twilight studies, to see how he continued to experiment with mood and luminosity. You might also dive into Claude Monet’s late-19th-century garden scenes to understand the techniques that inspired Sargent’s own experiments. And if you’re ready to go further, Tate Britain’s collection notes, contemporary letters, and Sargent’s preparatory sketches offer a rich next step into the world behind the canvas.