Isamu Noguchi’s Black Sun is often seen as a polished granite torus about nine feet in diameter, installed in Volunteer Park in Seattle. However, many have speculated on the symbolic meaning that echoes ancient history.

On the surface, Black Sun is simple: a circular ring, deeply black, with a hole in the middle. But its meaning drawing on both modern and ancient philosophical traditions.

Fact: Noguchi’s Black Sun is an interactive cosmic lens: depending on where you stand, the circular void perfectly frames the Space Needle, Elliott Bay, or the Olympic Mountains, turning the surrounding landscape into part of the artwork and inviting viewers to see the world through Noguchi’s meditative vision.

Ancient Suggestions & Symbolic Parallels

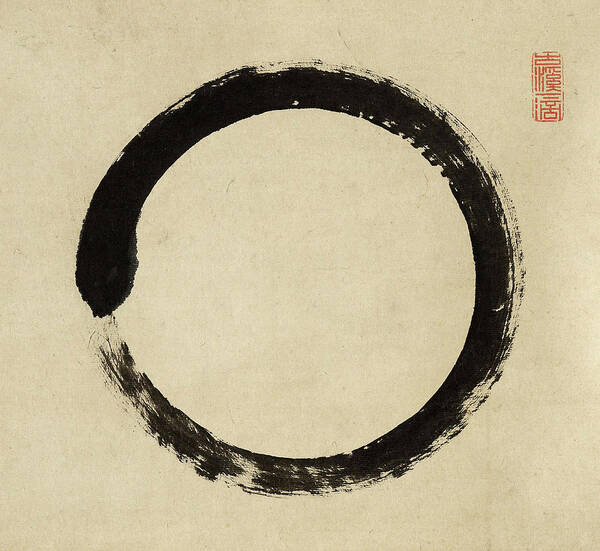

- Ensō: In Zen Buddhism, the circular form resonates strongly with the concept of emptiness (śūnyatā). This is different from “nothingness,” but as the understanding that all things are interconnected, impermanent, and without fixed essence.

- Sun Cross / Solar Wheel: Though not a cross, the circular “sun” shape nods to ancient solar motifs found in prehistoric European cultures. The prevalence of circular sun-disks in Neolithic carvings, Celtic ritual artefacts, and Scandinavian rock engravings shows that the circle was one of humanity’s earliest symbols for celestial forces.

- Taijitu (Yin-Yang): The idea of a circle as a cosmic symbol of unity and polarity resonates with Noguchi’s balanced ring, mass and void, material and space. Taoist, and early cosmological systems, the circle represents the totality of the universe, where opposites such as light and dark, form and emptiness, or matter and energy coexist in equilibrium.

- Japanese – maru (丸): In traditional Japanese symbolism, circles (“maru”) are also connected to the sun (e.g., the rising sun motif) and represent protection, wholeness, and continuity.

Death and Rebirth

Many ancient cultures marked the disappearance of the sun and its eventual return as profound symbolic acts, linking this cycle to themes of death, rebirth and transformation. For example, the winter solstice, the point at which daylight begins to lengthen again, was celebrated in ancient Egypt and across prehistoric Europe as the “rebirth” of the sun, highlighting that light must fade before it returns to fullness.

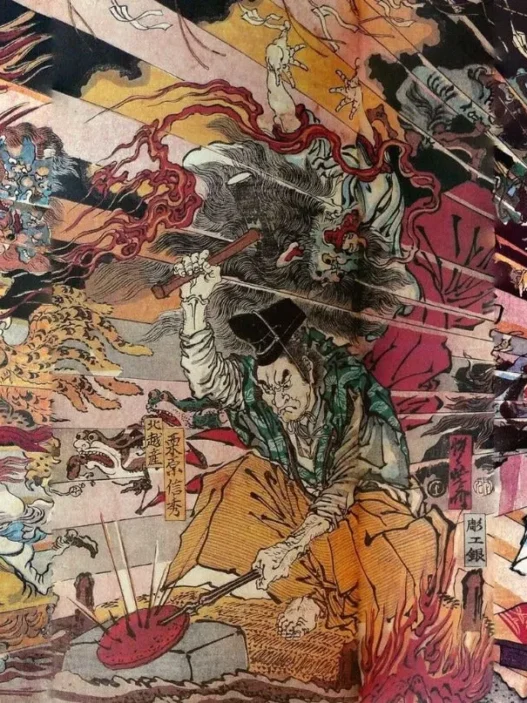

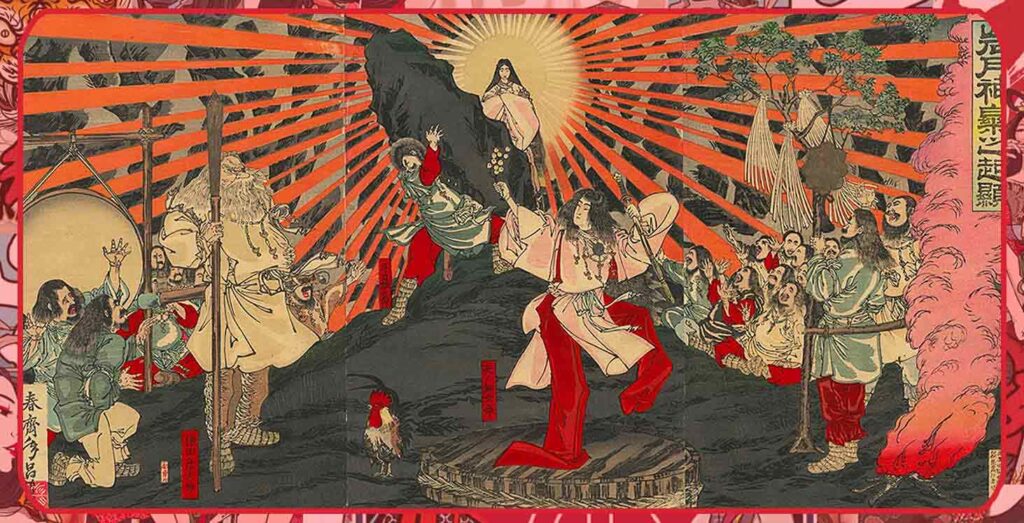

Similarly, the missing-sun motif appears in mythologies such as that of the Japanese sun-goddess Amaterasu, who retreats into a cave plunging the world into darkness before emerging to restore light and order.

These ancient patterns support the idea that the “Black Sun” can symbolise the death of the ego, the dark night before enlightenment, and the regeneration of the spirit, a descent into void followed by a return of illumination.

The Circle, the Void, and the Infinite

Noguchi’s use of the circle in Black Sun echoes the Zen Buddhist concept of ensō, a hand-drawn circle made in one fluid stroke that symbolises enlightenment, emptiness, and the universe.

In Zen, the circle is a meditative gesture that represents no beginning and no end, unity, and the void.

This idea of emptiness, or shunyata, is mirrored in Noguchi’s sculpture: the void in the center isn’t simply “nothing,” but a presence — a space that frames the sky, the city, and the viewer.

The Story Behind the Shot

Adams often photographed untouched wilderness, but Moonrise includes a living community, creating a powerful contrast between humanity and nature.

This tension raises symbolic questions: how small are we compared to the universe, what meaning do our lives hold within an infinite cosmos, and how do we create sacredness in everyday life?

The small adobe homes of Hernandez sit delicately beneath the immense sky, symbolising the fragility, brevity, and humble scale of human existence against the vastness of the earth.

Literature Behind Ansel Adams Moonlight

Bill Graeser’s “Magic Light” is a poignant tribute to Ansel Adams, evoking not only the photographer’s physical frailty but also his enduring inner vision. In the poem, Graeser imagines Adams raising his bony arm like a tripod to grasp his camera, chasing the golden light of sunrise and sunset.

What he calls the “magic light”.

By Bill Graeser

Ansel Adams sits up

reaches for his camera—

his arm bony as a tripod leg

for it is “Magic Light”

the golden light of sunrise

and sunset.

But then he lays back down

and focusing instead

through the lens of his soul

in the black box of his skull

he sees… all the light

that ever filled Yosemite

or blazed the crosses at Hernandez

and with his brittle jaw

with its few teeth remaining

there in the dark room of a coffin

he smiles.

“Magic Light” by Bill Graeser won the Iowa Poetry Association’s 2012 Norman Thomas Memorial Award. Bill posted it August 28, 2012.

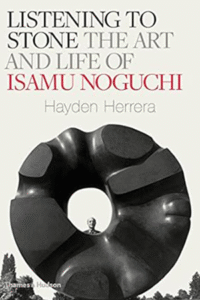

“Sculpture can be a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness.” — Isamu Noguchi

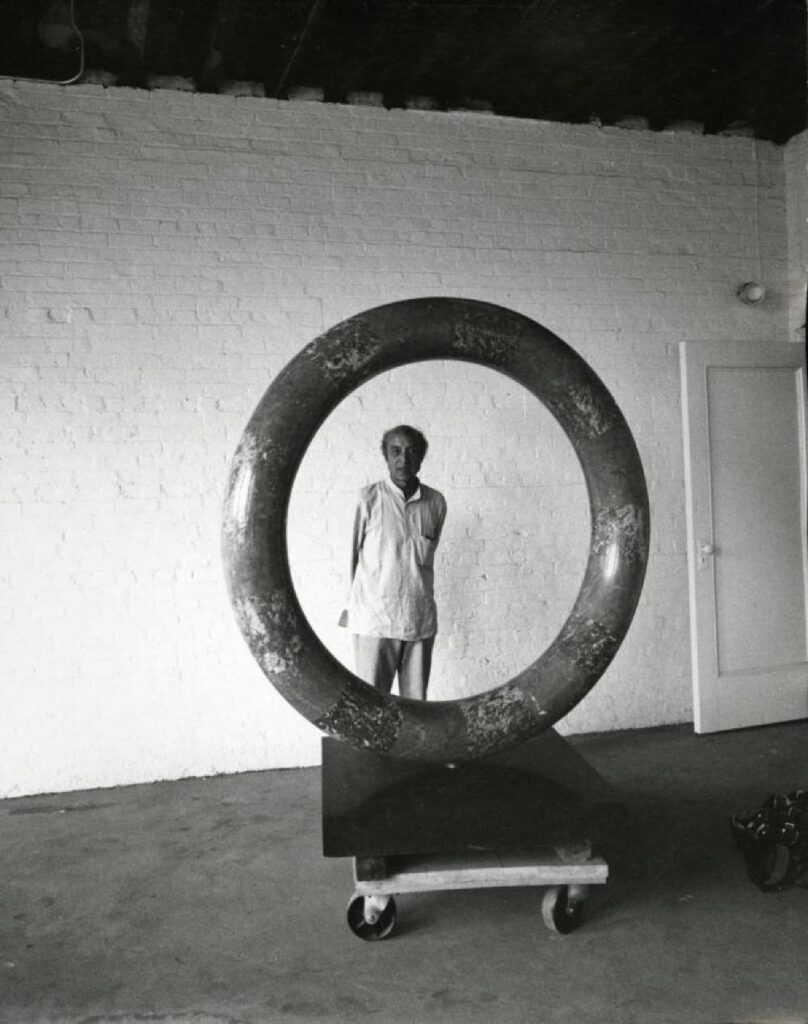

Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988), the Japanese American sculptor, was one of the most daring and influential artists of the 20th century. The Barbican Art Gallery is presenting the first major European touring retrospective of his work in two decades, a collaborative exhibition organised with Museum Ludwig (Cologne) and Zentrum Paul Klee (Bern), in partnership with LaM in Lille.

Spanning six decades, the exhibition traces Noguchi’s extraordinary creative evolution across sculpture, architecture, dance, and industrial design. It highlights his belief that sculpture should shape the way we live, offering immersive environments rather than isolated objects. Drawing from the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York, as well as important public and private collections, the show features more than 150 works, including stone and bronze sculptures, ceramics, wood carvings, theatre sets, architectural models, playground designs, and his iconic lighting and furniture.

While Noguchi is widely recognised for his modernist coffee table and Akari light sculptures, his practice was far broader and more experimental. He continuously pushed sculpture into new social, environmental, and spiritual dimensions. A true global citizen, Noguchi’s travels through China, Mexico, India, and beyond shaped his vision of art as an essential part of everyday life. Rare archival materials and photographs provide deeper insight into the artist’s life and values — revealing a humanist thinker whose cross-cultural heritage and curiosity reshaped the boundaries of modern art.

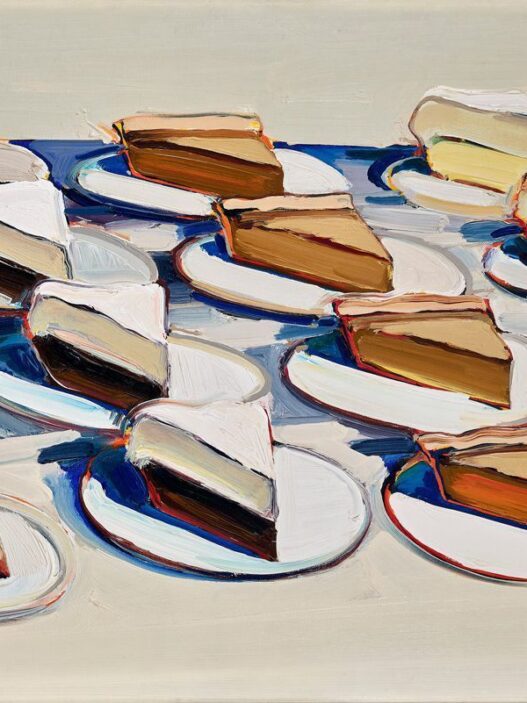

Related Works to Black Sun

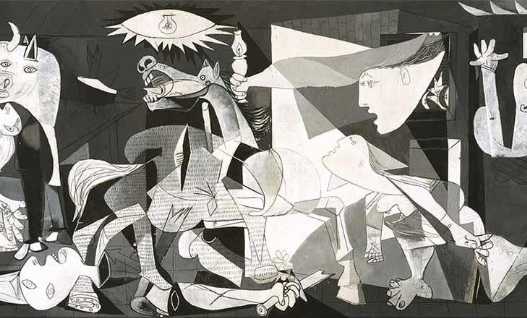

Several of Isamu Noguchi’s sculptures echo the cosmic symbolism and meditative presence found in Black Sun. One key example is Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars (1947), a visionary earthwork imagining a colossal human face carved into the landscape, a monument meant to be visible from space and a reflection on humanity’s fragility after World War II.

Another related piece is Sun at Noon, where Noguchi explores the sun as a distilled, abstract form, reinforcing his fascination with celestial geometry and universal symbols. His Akari Light Sculptures also carry this lineage; though softer and more domestic, their glowing orbs channel the same dialogue between light, shadow, and the void that defines Black Sun. Together, these works reveal Noguchi’s lifelong search for forms that connect the human world to ancient cosmologies, natural forces, and the timeless rhythms of the universe.

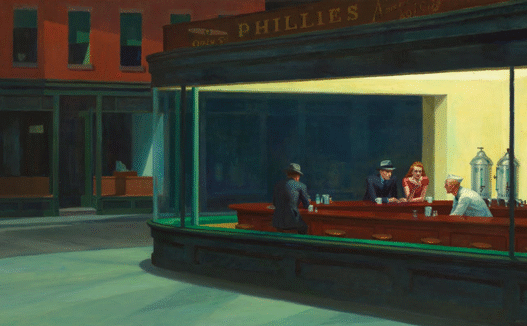

From the archives: Photographer Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams’ Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico remains one of the most studied photographs in art history because of the interplay of light and darkness, the juxtaposition of human presence against vast nature, and the eternal rise of the moon all convey themes of life, mortality, and transcendence.

One of the most asked questions about this photograph is, “Why is the moon so prominent in Moonrise?”

The answer lies in Adams’ intention: the moon represents constancy, eternity, and the cosmic scale that dwarfs human life, reminding viewers of our fleeting yet meaningful existence. Through this balance of earthly detail and celestial grandeur, Moonrise continues to captivate and inspire, making it a timeless masterpiece of symbolic photography.